|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

Alex I Askaroff Alex has spent a lifetime in the sewing industry and is considered one of the foremost experts of pioneering machines and their inventors. He has written extensively for trade magazines, radio, television, books and publications world wide. Over the last two decades Alex has been painstakingly building this website to encourage enthusiasts around around the Globe.

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

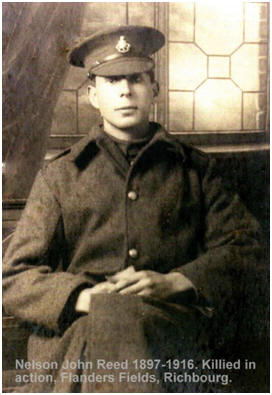

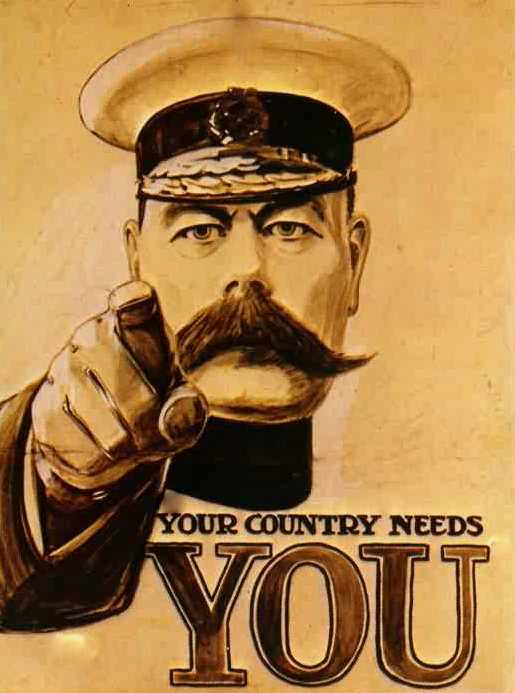

'Least We Forget' This is a little chapter of my wife's family history. It is worth noting down as there maybe other Reed's who would like to know what happened to Nelson. He was my wife's Great Uncle and this story was told to me by his sister Iris Reed (Cottington) who was still living when I was a boy. Iris often talked about her brother, the loved one who was lost. The only surviving photo of him is the one above. When I first saw the picture I was fascinated by it, the soulful looks of a young man a few weeks before his death. This is his story. The Lowther Lambs In September 1914, Conservative politician Claude Lowther, owner of Herstmonceux Castle, formed the Lowther Lambs regiment and set up recruitment offices all over Sussex. The Sussex lamb was their motto and mascot. Peter, the actual lamb, survived the war and was buried at Herstmonceux Castle in 1928 in the rose garden. Lieutenant Colonel Lowther did not follow his men to war. Nelson John Reed was living with his parents at 10 Eshton Road Eastbourne when he heard Lord Kitchener’s call to arms. His father, Jack, had been in the Light Horse Infantry and Nelson always wanted to live up to his dad and have adventures of his own. Nelson came from a family of military men and went with his mates to enlist at the Terminus Road Recruitment Office. However the queue was so long it stretched all the way from the railway station in Terminus Road, up Grove Road to the Town Hall. Nelson went home but the next day he walked all the way to Bexhill with three of his mates where he eventually enlisted. He, like so many young men, was eager to fight for his country. The volunteers, who were almost entirely from Sussex, formed the 11th, 12th and 13th Royal Sussex battalions of the 2nd Southdown Regiment raised in late 1914. They were part of the 116th Brigade of the 39th Division. Over 600 men from the 12th battalion were friends and relatives from Eastbourne, especially the Seaside end of town known as the East End. The 12th soon became known as the ‘Pal’s Battalion.’ The men were initially based at Cooden Mount Camp, Bexhill, where they received some of their training from recently promoted Sergeant Major Nelson Carter. The mood was optimistic and cheerful and even a song was penned to Colonel Lowther, called Lowther’s Own.

Oh, the Sussex Boys

are stirring in the woodland and the down,

Nelson Carter Nelson Reed and Nelson Carter were local lads, Nelson Carter’s parents, before moving to Hailsham, lived in Latimer Road (Nelson family had lived at 33 Greys Road, Old Town) and Nelson Reed’s family in adjoining Eshton Road. Both the families knew each other and both Nelson Reed and Nelson Carter were to train together and die together. Nelson Carter was ten years older than Nelson Reed being born on April 6, 1887. Before the outbreak of the First World War Nelson Carter had walked from his home at 33 Greys Road in Old Town, past St Mary’s church, where he had married Cathy and had his daughter Jessie baptised, to work as a doorman at Old Town Cinema, along the High Street, near the Old Star Brewery. It was renamed in 1921 to the Regent Picture House and then the Plaza. All the local lads looked up to and respected the older, highly experienced, Nelson Carter. He was a tall powerful man and had tattoos from his previous trips with the army abroad, one of Buffalo Bill who he saw when his troop visited Eastbourne and a saucy one of a semi naked lady from a tattoo parlour on one of his more exotic military expeditions. The lads would always want to see the saucy tattoo when they used to chat outside the cinema or later on parade. Some of the lads that enrolled were still children, like John Searle in the battalion, who was only fourteen when he enrolled underage! Nelson Reed had just enough time to get his picture taken at a professional studio in Seaside and ask for a copy to be sent home to his proud mum and dad. The battalions travelled to France in March 1916 landing in Le Havre where they received further training before moving to their trenches in Northern France at Richebourg L'Avoue. Here bombs fell, rats nibbled at their rations and gas came across from the enemy. Morning rum rations were issued and letters were written home disguising how bad conditions were. Snipers strained for any poor soul that peered over the trenches. Drinking water was carried across in petrol cans stinking of fuel. No baths or clean clothes. The reality of war was biting.

The Somme

Diversion Many people know July 1st 1916 as the start of the bloodiest event in our military history but it was in fact Saturday June the 30th that the battle of the Somme really started with a diversionary attack to the north at Ferme du Bois, Boars Head, near Richebourg a few miles from Lille and part of Northern France, Belgium and Netherlands traditionally known as Flanders. It was called Boar's Head as that was shape of the outline on the maps. The Battle 'Lambs to the slaughter' The fateful day on June 30th started with an hour of sustained bombardment of the enemy. As Sussex went ‘over the top’ to the sound of whistles blowing, it was to be Nelson’s first and last military action. Still dark, early in the midsummer morning the whistles blew along the line to signal the attack by the 11th, 12th and 13th Southdown battalions of the Royal Sussex Regiment. Thousands of men shouting, “For King and country,” went up the ladders towards the enemy and into the barb wired, mined, nightmare hell of No Man’s Land. Nelson and the 12th Battalion attacking the front line at Ferme du Bois, Sadly, security was virtually non-existent in those days and the Germans knew exactly what they intended to do. The shelling the afternoon previous and the early bombardment in the dark was a typical announcement of an immanent attack. Some say that the Germans were not waiting and unprepared for the attack. Family oral history tells a very different story. Several of the men that returned told Iris a similar tale. Just before the attack, still dark, as the men prepared to go over the top they could hear the Germans shouting in broken English, “Why are you waiting Tommy, we have some surprises for you, come and get them Tommy!” This greatly unsettled the young men who had hoped the sustained bombing would have weakened their defences and possibly caused them to retreat. To hear them so clear and so close was deeply worrying. As they came out of the trenches, just as lieutenant colonel Grisewood commander of the 11th had fatally predicted, they were mown down by rapid gun fire. Machine guns had been set up to fire diagonally across the approaches making it nearly impossible to break through to the enemy lines. Grisewood had earlier refused to send his men to slaughter and been summarily dismissed before the action (it probably saved his life). The Germans had positioned their water cooled machine guns behind concrete barriers. Firing across each other they made a curtain of death that few would survive. After the failed, “surprise attack,” many wounded tried to get back to the relative safety of their own trenches but they were then targeted by German artillery and blown to pieces. In the carnage most of the officers (at least 17) in Nelson’s battalion had been killed during the first charge, within minutes of the attack starting. This left company sergeant Nelson Victor Carter in charge of the remaining 12th. Back in his trench and now in command Nelson was in a fury at what he had seen and desperately wanted to gain some small measure of success out of the wretched situation. His surviving men were still wound up and ready to follow him. As the smoke screen intensified Nelson Carter made the decision to attack once again. What was left of the 12th and 13th battalions regrouped for the charge with the 11th Battalion supplying back up and carrying parties for the wounded. Nelson Carter and his men made a gallant fourth charge laden with hand bombs and what little ammunition they had left. With Nelson Reed and his mates following closely behind they managed to get across No Man's Land but much of the barbed wire was still intact and many of the muddy trenches became impossible to cross because the specialist carrying parties (sent out earlier to clear pathways and make temporary bridges) had been slaughtered in the first wave. The whole attack was turning into a nightmare. However under heavy shellfire, and as the German machine guns sprayed bullets into the smoke, Nelson and a small band of men managed to make a penetration into the enemy’s front and second lines. Once in they cleared German trenches. The group were comparatively safe, for a while. Nelson Carter could see that the other battalions had been wiped out so holding his position was futile. Most of his men were either dead, wounded or trying to crawl back to safety. Also, the retreating Germans (as they fell back) had sent up SOS flares for artillery support. Enemy heavy guns then opened up on the new positions of the remaining Lowther Lambs. Nelson Carter and his men were heavily outnumbered by a well dug-in enemy. With no back up, no ammunition, and total carnage and death all around, withdrawal was the only option to save the last of his battalion. By 7.30 am, and now in full light, with no cover Nelson Carter and his small remaining group decided to try and get back to their lines before the main German counter attack. However just before retreating, Sergeant Major Nelson Carter saw that one of the German machine gun nests close to him was causing severe casualties to his men in No Man's Land, mowing down any soldiers trying to run. Only Nelson Carter had any ammunition left in his revolver. With bayonets fixed the small group waited for the machine gun to run out of ammunition. They knew that they had a few seconds in which to rush the Germans. As the enemy stopped to reload Nelson's team ran like madmen to attack the Germans. Nelson shot two of the gunners as another escaped under the netting. He then shouted orders to his men to get back to their lines. He stayed, turned the machine gun round and used it on the enemy. As his lads ran he shouted encouragement to his boys struggling back to their trenches. His outstanding act of bravery allowed a few of his men to get back safely. Nelson Reed's & Nelson Carter's Deaths As Nelson Reed and his mates made their way back to their own lines a fatal error occurred. More smoke, put up by the British for protection, drifted across No Man’s Land making it impossible for the confused men to find their own trenches. The Germans then opened up with another heavy barrage of bombs straight into the middle of the men. It was in this place of hell, smoke, mud, barbed wire, bombs and bullets that Nelson Reed and his pals died. Moments later Nelson Carter miraculously made it back to his trenches untouched. However seeing the carnage that his fellow soldiers had endured he jumped back out of the safety of his trench and started to drag wounded soldiers back. With no thought for his own safety, he made several spectacular runs into No Man’s Land to retrieve his wounded colleagues. Nelson carter was a powerful well built man and was able to throw a wounded soldier over his shoulder and run. Many of his wounded colleagues cheered him on as he went out time and time again. However the smoke started to drift in the wind and became patchy which allowed the enemy to spot what he was doing but Nelson never stopped. After bringing back at least seven men, Lieutenant Howard Robinson, Nelson’s wounded commander who was slumped in a trench, saw Nelson breathing heavily as he crawled once more out of the trench and stood up. As the smoke drifted he desperately looked to see if there were any more of his men that he could save. While he was standing on the edge of the trench he was hit by a sniper bullet and fell back, dead. Some say that he was only wounded and died later but his surviving friends agreed that Nelson had died quickly after being hit. Nelson Victor Carter and Nelson John Reed, like hundreds of others, had died within yards of each other, comrades in arms to the end. The battle was over for the blood soaked earth of Richebourg. There had been no ground gained from the action! The first soldiers had gone over the top at just after 3.00am and the fighting was over within a few hours. During that short period, over 1,300 Sussex men were killed, wounded or missing. There was hardly a town or village in Sussex that did not lose their young men. Even the Germans buried some of the dead Sussex men who they found behind their lines. Many call it the day that Sussex died. Nelson Carter was given a posthumous Victoria Cross for his actions and bravery, he was 29 when he died. Over 30 other medals were awarded for the outstanding conduct and bravery shown on that day. Nelson carter's grave is in the Royal Irish Rifles Churchyard in Laventie, France. Nelson Reed has no known grave. Press reports and propaganda at the time was ridiculously optimistic and originally boasted of success with few casualties. In fact only 47 casualties were reported in the local paper. As worried parents waited for news worse was to follow. July 1st 1916 heralded the mass slaughter and the beginning of the Battle of the Somme on the Western Front. 750,000 British and French soldiers climbed out of the comparative safety of their trenches and attacked all along the Western Front. The battle of the Somme had begun. Within five months and with less than eight miles of land captured the combined armies of France and Britain had lost over 600,000 men. Douglas Haig, British commander for the Western Front made it clear that every position, every muddy hole, and every trench must be held to the last man! Men failing in their duty would be shot at dawn. Such was the total carnage that it was not until August that Nelson Reed was officially reported missing in action in the Sussex Daily News. Just before Christmas 1916 Jack and Emily Reed received the dreaded piece of paper, form B101-82… Dear Sir it is my painful duty to inform you of the death in action of your son Nelson. J Reed of the 12th Royal Sussex Battalion on the 30th June 1916. Later his medals and death penny arrived but they were cold consolation. Nelson Reed’s body, (like Rudyard Kipling’s son and countless others during WW1) was never identified. He lies amongst the dead in Flanders Fields that mark our bloody road to freedom. At Pas de Calais there is the Loos Memorial to mark where so many brave souls lost their lives. The casualties were so high amongst the decimated Sussex 11th, 12th and 13th battalions that they were disbanded. The remaining brave men of the Southdowns carried on fighting until they were finally disbanded in early 1918. It had taken nearly six months before Jack & Emily had been notified of Nelson's heroic but pointless death. Six months that they had hoped beyond hope that their son lived, perhaps wounded somewhere or captured. As more and more local lads returned from the Front, Jack & Emily gathered the full story of how both Nelson's had died. They later told these stories to Iris, Nelson's little sister who passed them on to me. Nelson John Reed was just 19 when he gave his life for King and Country in Flanders Fields at Richebourg. A service was held at Christchurch, Seaside, where he and many of his pals are remembered in the chapel. His name (though miss-spelt) is also at the Town Hall memorial.

In Flanders fields the

poppies blow

We are the Dead. Short days

ago Nelson John Reed 1897-1916. Killed in action, Flanders, Richebourg. Nelson John Reed KIA 19yrs old

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

Well that's it, I do hope you enjoyed my work.

His full story is in

Have I Got A Story For You. I have spent a lifetime collecting, researching and writing these pages and I love to hear from people so drop me a line and let me know what you thought: alexsussex@aol.com. Also if you have any information to add I would love to put it on my site. Fancy a funny read: Ena Wilf & The One-Armed Machinist A brilliant slice of 1940's life: Spies & Spitfires

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

CONTACT: alexsussex@aol.com Copyright © |

|||||||||||||||||||||