|

||||

|

|

Alex has spent a lifetime in the sewing industry and is considered one of the foremost experts of pioneering machines and their inventors. He has written extensively for trade magazines, radio, television, books and publications worldwide.

LOOK...

OUT NOW!

Most of us know the name Singer but few are aware of

his amazing life story, his rags to riches journey from a little runaway

to one of the richest men of his age. The story of Isaac Merritt Singer

will blow your mind, his wives and lovers his castles and palaces all

built on the back of one of the greatest inventions of the 19th century.

For the first time the most complete story of a forgotten giant is

brought to you by Alex Askaroff. |

|||

|

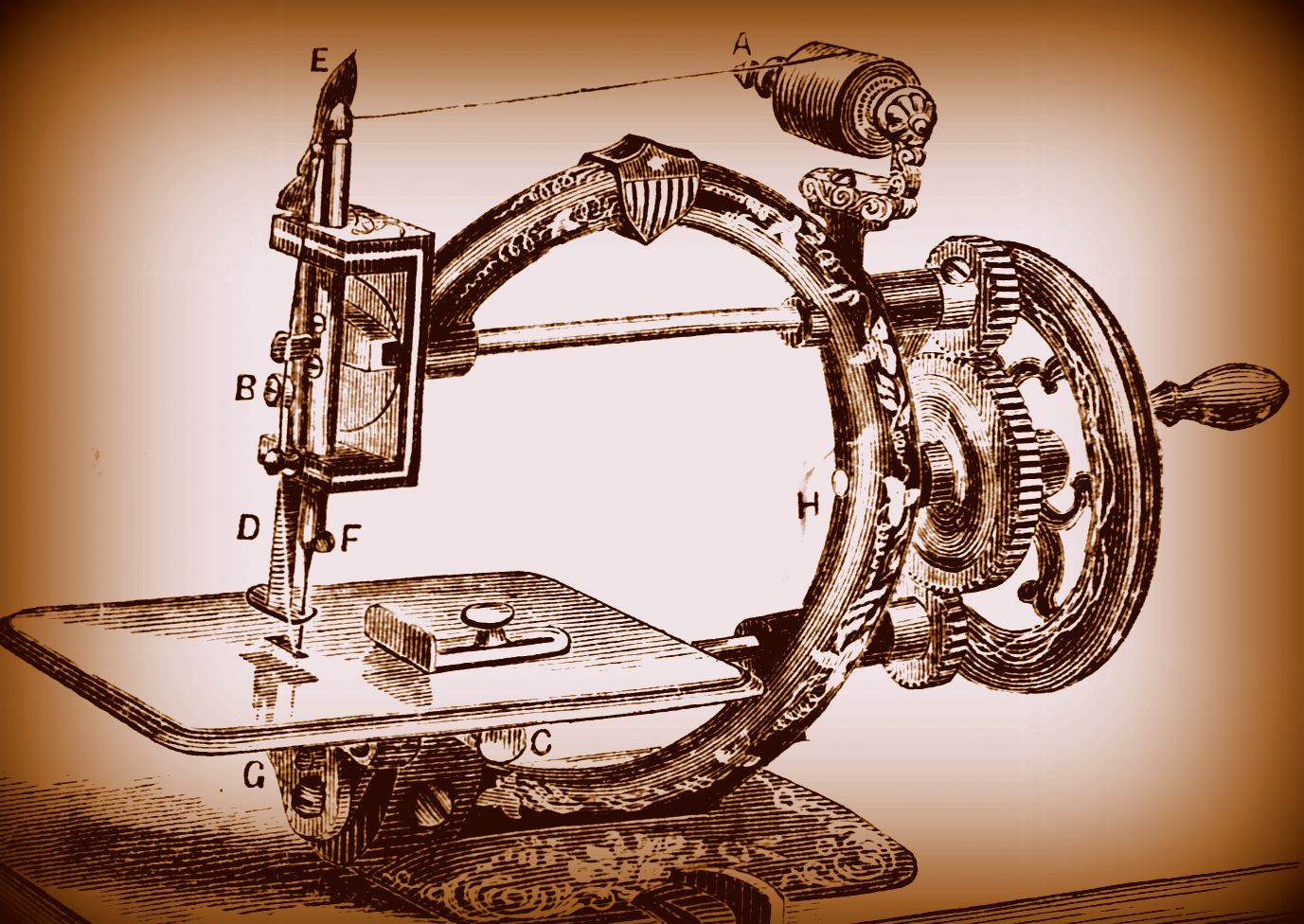

Johnson Sewing Machine 1855 Johnson, Clark & Co New England Machines by Alex Askaroff

Thank You It would be impossible to write all these research pages for you without the help of other experts, specialists and enthusiasts around the world. This page has taken over 30 years to complete with the help of my old mentors Graham Forsdyke & Maggie Snell in London, England, patent specialist André Grahl in Germany, Michael Jay Wolfgang Anderson in New Hampshire, USA, Wayne Schmidt in Southern California, USA, Dr Martin Gregory in Winchester, UK and many others. When I use an image from a collection I mention the collection in the image. I have only scratched the surface but I hope it will allow others in the future to find the hidden paths that lead to some of our greatest sewing machine pioneers.

A quick breakdown of the following blog is as follows. Established around 1855 as A F Johnson, then A F Johnson & Co, the business became the Gold Medal Sewing Machine Company with Johnson, Clark & Co. the company then became New Home. The business rolled on being taken over, combined and bought out. They were connected with the Free Sewing Machine Company and in 1953 merged with the National Sewing Machine Company. The business that started way back in the 1850s was eventually bought out by the Japanese, Eye-of-the-Snake company, Janome. Janome continued to use the New Home brand on some of its fabulous machines. let's take a breath and slow down. It's time to look at this fascinating story in more depth. From the middle of the 1850s, over a dozen makers in the same New England area of the United States all started making similar sewing machines. Castings were often bought from central suppliers and parts were also shared. All the machines were subtly different but looked similar. There was a reason for this. The Sewing Machine Kings were on the warpath and prosecuting as many small manufacturers as possible (to eliminate competition). A ‘war-chest’ was put aside by the Sewing Machine Cartel (run by the powerful few, like Isaac Singer and Elias Howe) to stamp out any and all new sewing machine makers.

It worked like a charm, most of the companies failed, changed hands and key people quietly moved from one business to the other. Raymond, Folsom, Grout, Wilson, Shaw, Barker, French, White, Clark, Wheeler, Johnson, Bartlett, Davies, Nettleton, Goodspeed, Wyman, Robinson, and many more were involved in these early New England machines. Tiot Judkins came over to England from Massachusetts to make a New England copy to sell in Europe. The names of the sewing machines also changed, Common Sense, American, The Fairy, Globe, Pride of the West, Family, and countless others were used to sell the similar chain-stitch models. Samuel Barker called his model the Brattleboro sewing machine while Nettleton & Raymond’s New England sewing machine was the Common Sense. Joseph W Bartlett did surprisingly well for a while in Winchendon, Massachusetts with the Bartlett Sewing Machine Company before changing to producing street lamps!

Cleverly the New England makers kept on the move and made multiple changes to their machines. Although the basic looper, feed and tensions remained similar, the shapes and castings altered. This gave the Sewing Machine Combination or Cartel a real headache. Because supplies were small and often direct to the customer, prosecuting the New England chain-stitch makers was as difficult as catching moonshiners during prohibition.

When things in America calmed down, patents expired and pioneers like Howe and Singer died, the remaining few established makers started paying for patents and licenses. Being legitimate manufactures they also started marking their machines. This makes things so much easier for collectors, researchers and enthusiasts. By the middle 1860s the surviving New England chain-stitch sewing makers were firmly established and we see makers like Folsom and Johnson clearly marking their machines.

The few entrepreneurs that survived the Sewing Machine cartel onslaught flourished. Charles Raymond had skipped across the border to Canada to avoid prosecution and did very well. You’ll have to read my book on his amazing journey. Others also grew. The most famous by far was the long forgotten sewing machine pioneer Albert Johnson. He has a small connection to the Japanese company, Janome, we shall talk about that a little later.

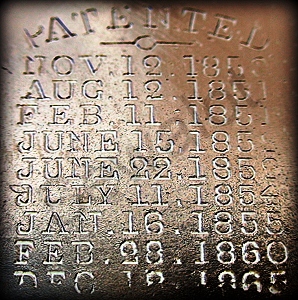

The company was originally a one-man band but as business grew Albert Johnson later joined forces and A F Johnson & Co became Johnson & Clark of Orange, Massachusetts. Initially producing several unique sewing machines including the Gold Medal Sewing Machine (which was actually several different machines) and the New England style chain-stitch sewing machine. They also made the Octagon sewing machine & Bartlett Sewing Machines using various patents from other sewing machine manufacturers. See my Dolly Varden Page for more on Home Sewing Machines. A F Johnson sewing machine patents

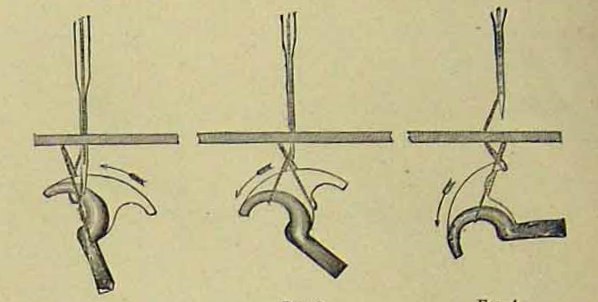

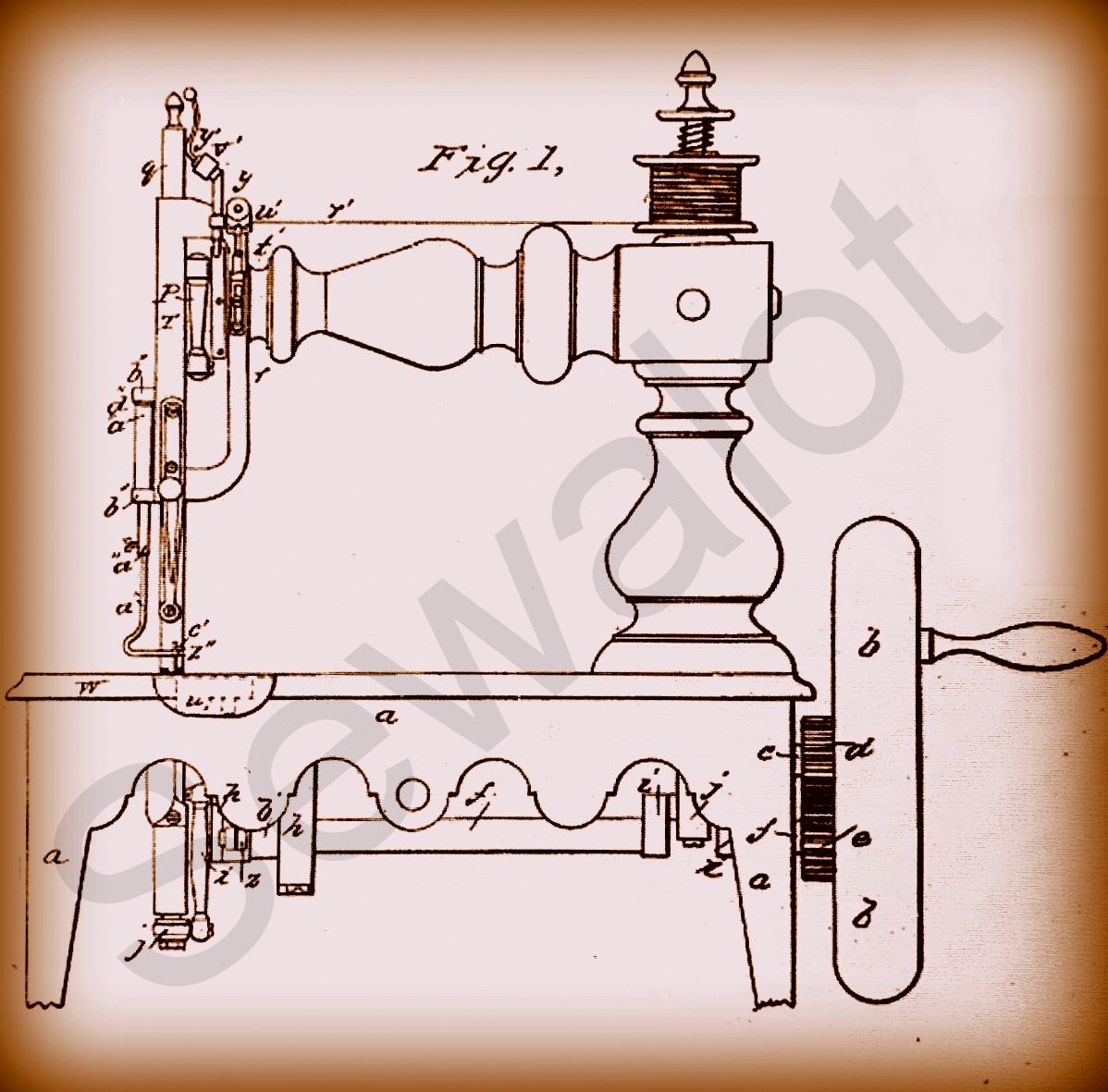

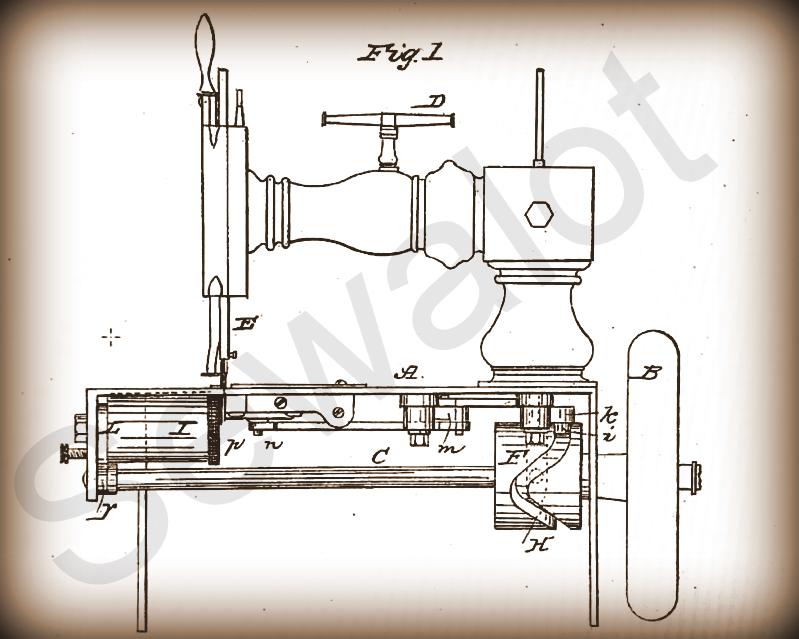

A F Johnson played a fascinating part in the development of the sewing machine during the 1850s. This included a major battle with the inventor of the 'elastic chain-stitch', James Edward Allen Gibbs. All the ‘lookalike chain stitch machines’ became commonly known as ‘New England’ machines. Most used a system similar to the Raymond looper design to catch and form the stitch. Tying down the actual makers is difficult. Businesses that only lasted for a short period before collapsing have left behind tantalizing trails, mainly in the machines that survive. Unique differences in the machines, that no others have, are the clues that point to the makers. Of course, many of the early machines were being made as the American Civil War raged. All were hand-built, some in little more than sheds, workshops and barns. When these closed all trace of them were lost forever.

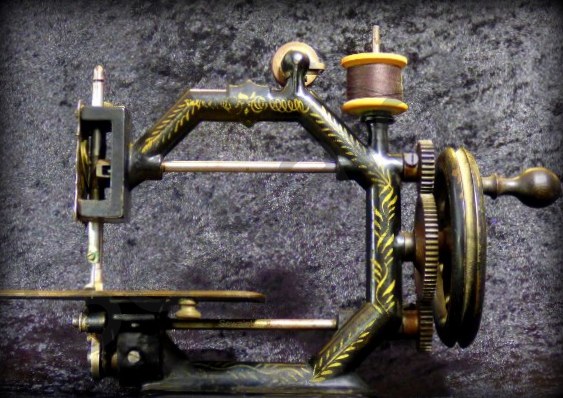

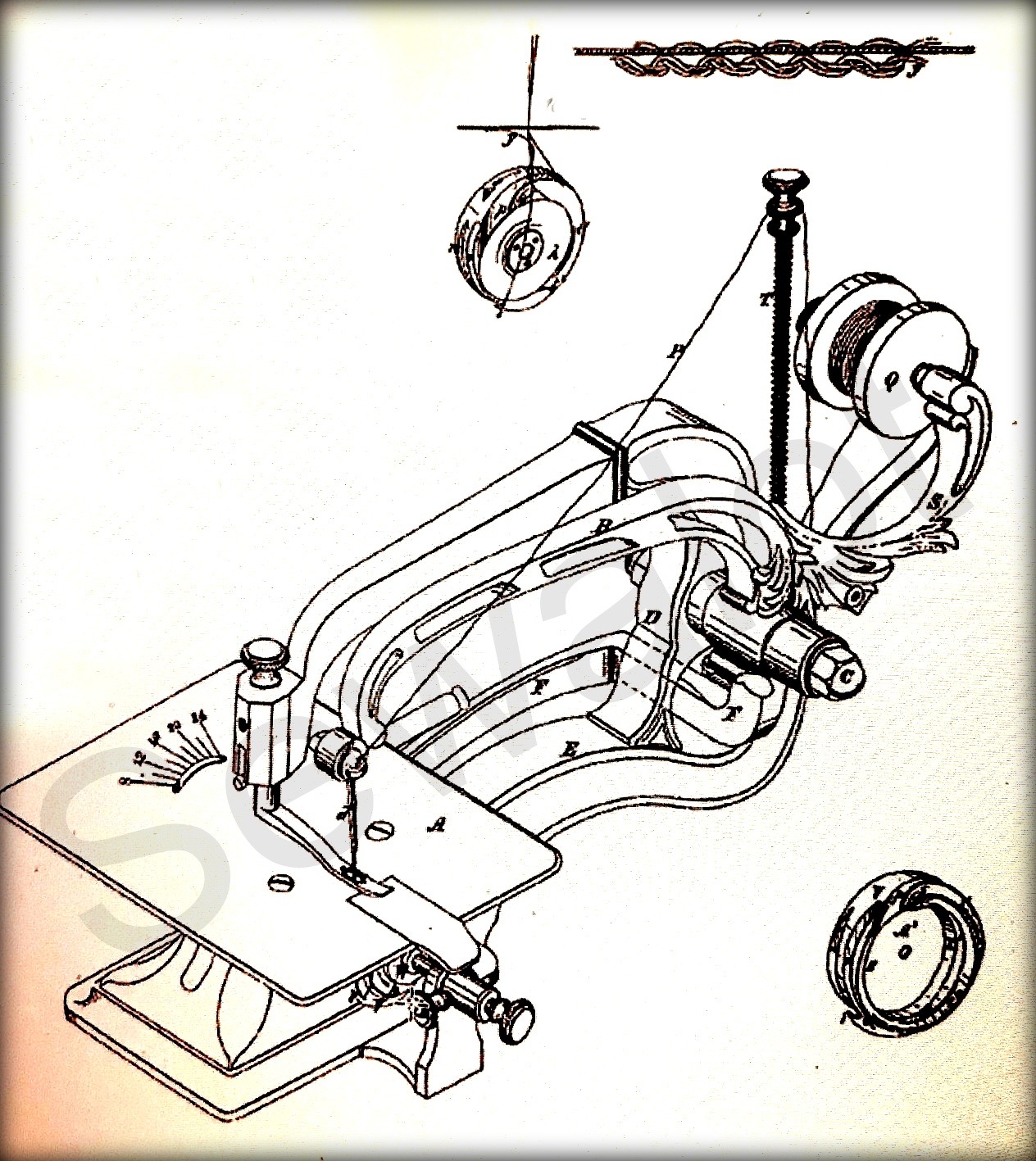

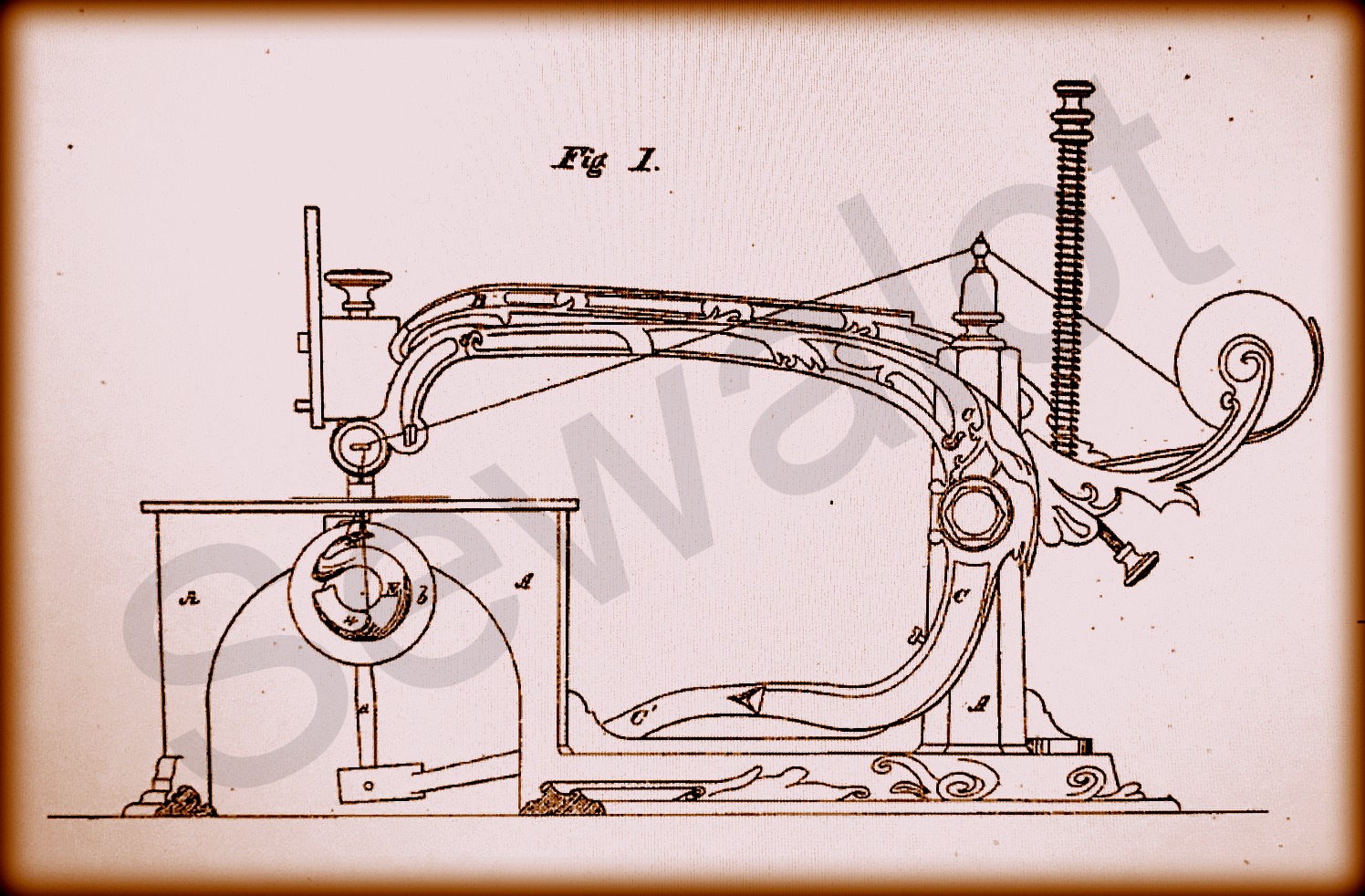

Identifying New England sewing machines is a minefield. Everyone from the greatest museums to experts have got it wrong more than once (including me). The Internet is full of misdirection and mistakes that lead people up the wrong garden path. I ended up writing a whole book just on Raymond-Weir sewing machines (which included a few of the European makers who copied the New England style) just to clear up a few facts. So you can see how complex the subject is just on this tiny narrow section of sewing machine makers. A F Johnson One of the first men in the sewing industry (and one of the more obscure early New England sewing machine makers) was Albert F Johnson. He is a bit of a mystery. We do know that many of his chain-stitch machines had a wasp-waist bed, a unique shape shared between Folsom, Johnson and a couple of others. This can be spotted when one comes up for auction. I picked a model up from a German auction mistakenly advertised as a Weir. Lucky me. A common story amongst pioneering sewing machine makers is the way that many started. A F Johnson was no different. He started making his New England machines in a tiny workshop around Millers River, Orange, Franklin County, Massachusetts in the early 1850s.

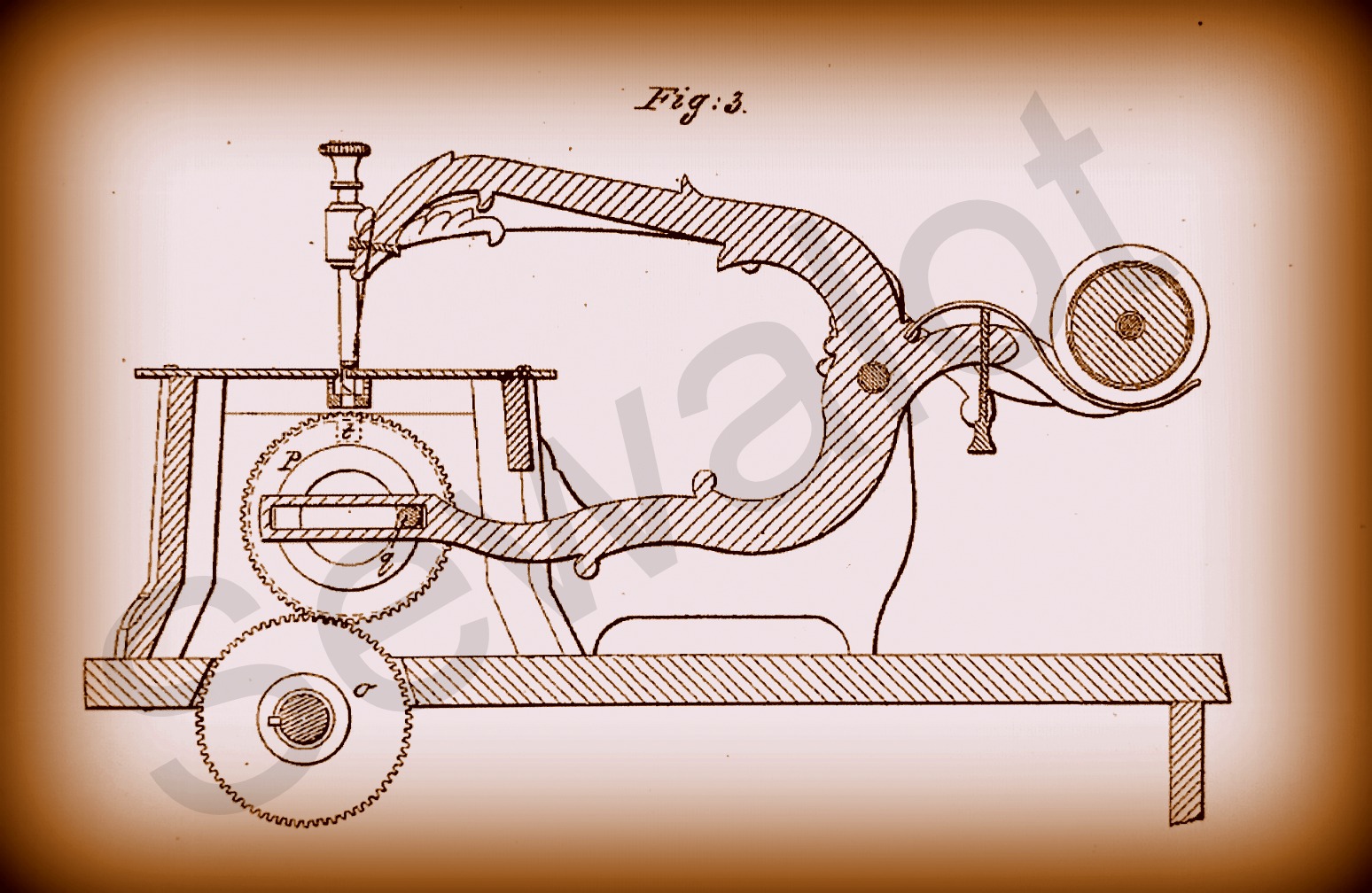

Through hell & high water by 1860 he was established as a main manufacturer of sewing machines. Legend goes that, as he had no forge, he bought in his castings and could only afford a few at a time. In his workshop he had a second hand lathe, bench press and some assorted tools. There he would make up all the parts needed to build his basic sewing machine. Once he had them working, he would load up his buggy and hit the road. When they were sold he would have enough money to order more castings and gears to make more machines. He started his machines at No1 with a stamped number on the base of each one.

As the business grew his most successful model became a 'double elastic stitch' sewing machine which he named the Gold Medal Sewing Machine after it won an award. In 1860 he was awarded a gold medal at the Massachusetts Charitable Mechanic Association Exhibition. An exhibition to promote local businesses. The machine used the 1856 & 1858 Johnson ‘improved chain stitch looper’ patents. As the looper turned it naturally twisted the thread, creating what Johnson sold as ‘the double elastic stitch’. This gave stretch to the stitch in the fabric. It was a great selling point BUT and yes it’s a BIG BUT coming… All was not well with Johnson. His first revolving looper patent (awarded the same year as Gibbs in 1856) had ended him in court against one of the Sewing Machine Cartel. James Edward Allen Gibbs went for the throat to try and destroy Johnson. They had both been awarded patents for very similar devices. Both revolving loopers gave the same twisted thread ‘elastic stitch’. In reality they looked quite different, which is why they were both given Patent Office protection. However, Gibbs saw the chance to crush his rival and took it. He had almost unlimited funds at his disposal. Albert Johnson was just a struggling small business man. The court judgments rolled on, thousands of court manuscripts were put forward in case after case. By 1859 Albert Johnson was broke. He had already sold half the right to the looper patent (possibly to Clark) but now sold the remainder of his rights. By July of 1859 he had no control over his best patent or any financial interest in it. Still the court cases rumbled on.

We have to jump ahead to 1872 just for a moment. Over 7,000 printed pages of testimony and court papers had accrued in this constant battle over who actually invented the revolving looper. On the 17th June 1872 (years after Johnson had left the sewing machine trade) he was in court again. Johnson was trying to extend his patent rights for a third time (paid by the company that owned the rights, probably New Home). Gibbs was still hard on his tail. He had used every trick in the book to destroy Johnson, including temporarily relinquishing his original patent on condition he could re-submit it. Brilliantly the re-submitted patent incorporated most of Johnson’s looper! This meant in future court battles (with different judges) the decision would be far clearer cut in Gibbs’ favor. It would look like Johnson's slightly later 1856 patent was a direct copy of Gibbs. However Judge Leggett was a smart cookie and worked all this out. He had read enough of the original court paperwork to see what was happening. Much to the annoyance of Gibbs he allowed Albert Johnson’s patent further protection granting him his extension. Although Johnson probably had little to gain from this 1872 judgment it did establish him for all time as one of the main inventors of the revolving looper.

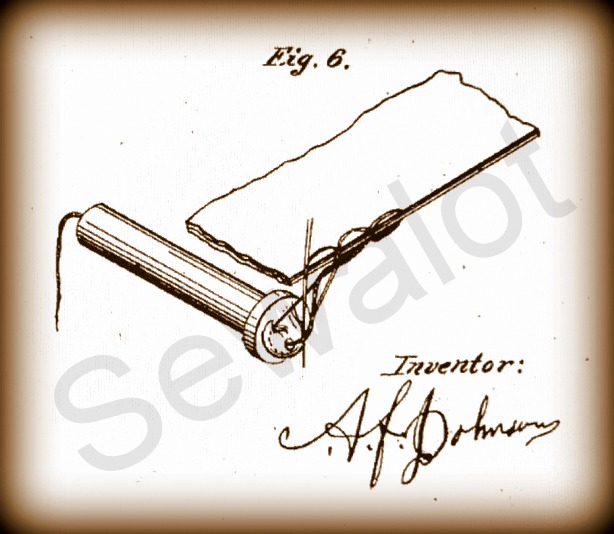

So now let’s get back to our sewing machine story. It is 1860. With huge demand and an expanding range, Albert took on associates and staff and the A J Johnson & Co business was formed. Later Johnson had taken on a partner and the Johnson, Clark & Co business was incorporated. It grew rapidly with several successful patent applications. A F Johnson sewing machine patents 26 Aug 1856 Pat 15635 25 Nov 1856 Pat 16120 This patent lead Johnson into court with Allen Gibbs as although it was approved it was very similar to Gibbs revolving hook. 23 Dec 1856 Pat 16315 13 Jan 1857 Pat 16387 22 June 1858 Pat 20686. 24 Jan 1860 Pat 26906. A brand new stitch combining a shuttle and chain stitch called a locked chain stitch. 24 Jan 1860 Pat 26948. Rotary hook & bobbin in conjunction with previous patent. 23 Oct 1860 Pat 30478. Revolving double thread chain stitch using three threads. 22 Jan 1861 Pat 31209 28th May 1861 Pat ? Albert was awarded patent protection on part of his Gold Medal machine. Johnson & Bartlett patent for three thread sewing machine. 12 April 1864 Pat 42292. Heavy duty leather machine with awl to puncture holes.

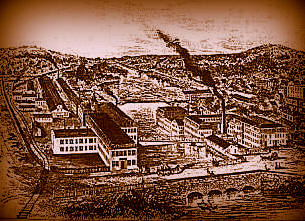

With the growth of the business, a new factory and with the arrival of more staff, investors and partners, Johnson, Clark & Co flourished becoming the Gold Medal Sewing Machine Company (named after its bestseller at the time). However all was not well within the partnership.

1867 was a good year for the Gold Medal Sewing Machine Co. As well as using patents under license, the company had over 20 patents worldwide. In the beginning the business had changed multiple times but had become firmly established as the Gold Medal Sewing machine Company. Interestingly original ‘double elastic’ Johnson Gold Medal sewing machines are extremely rare today. They were possibly produced from 1855 to1865, all were hand built and few survive. The business had their main sales agency at 332-334 Washington Street, Boston.

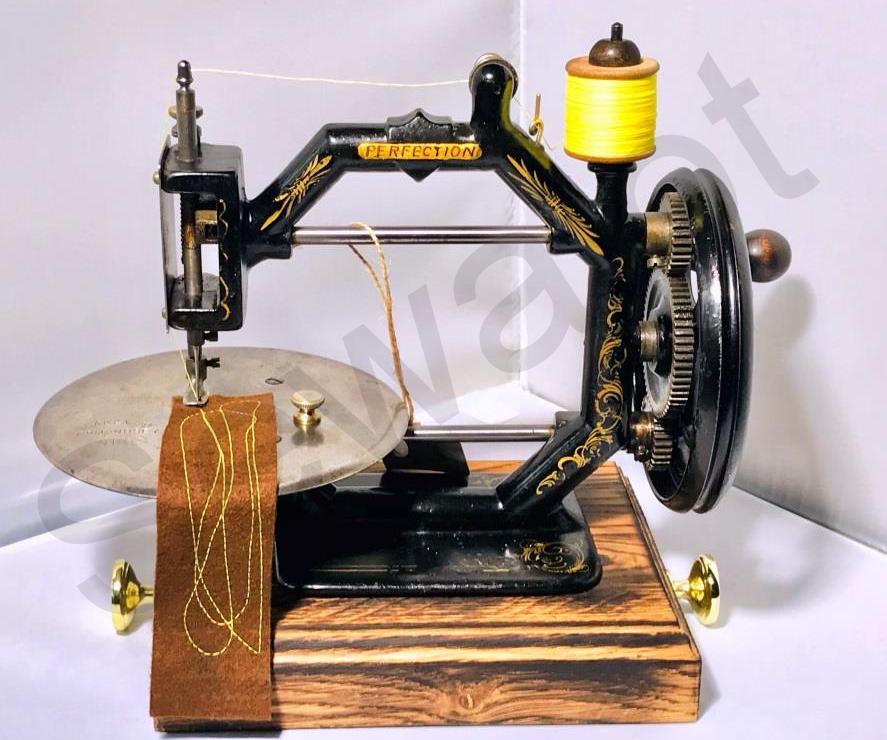

This super-rare image is with kind permission from Michael Jay Wolfgang Anderson and is now part of the Gary C Wacks Collection Interestingly, later Gold Medal sewing machines made by the later company had little to do with Albert’s original 'rocking arm' curved needle ‘double elastic’ gold medal winning machine above. The models were now octagonal and may have even been called the Gold Medal Octagon sewing machine. Some came with oblong beds and some with circular beds. The machines were also cheaper to produce using a more basic chain-stitch and came with the improved L L Davies patented hook mount. The small cheap models sold well and are the main machines that turn up today. Saying that, they are still extremely rare. The Gold Medal Sewing Machine Company Around the late 1860s Albert Johnson stepped back from physical participation in the sewing machine world. People say that William Barker and Andrew J Clark had managed to buy out Albert Johnson's business. With it they had bought all his machinery and his last patent rights too. By combining what originally started as competing businesses with William Barker, Thomas White, William Grout, Albert Johnson and Andrew J Clark, one consolidated business was formed. The Gold Medal Sewing Machine Company and Johnson, Clark & Co became one and the same. You have to stop for a second and understand that White, Grout, Johnson, Barker & Clark all had their own little businesses. Some failed some prospered some combined forces. Grout and Barker sold machines for White from a small workshop situated in East Templeton in Massachusetts. White also worked with French where they produced the New England Family Sewing Machine. Barker then combined with Clark to sell their Pride of the West New England chain-stitch. The Pride of the West sewing machine

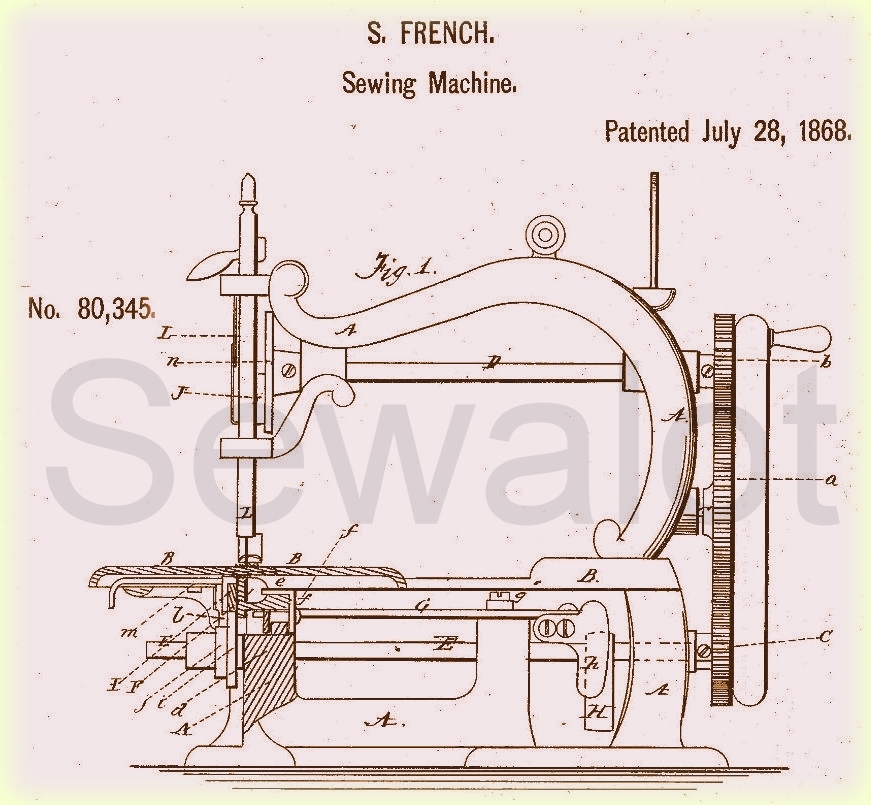

I know I know its like a bad game of Cluedo. Next thing we know it will Professor White in the dining room with a spanner! However by 1876 things got a little easier to follow. By the spring of 1867 a new company was formed and in July of 1867 Andrew J Clark, backed by W Barker, was elected president of the Gold Medal Sewing Machine Company, centred around Orange, Massachusetts. John Wilson Wheeler became secretary and treasurer with Stephen French, works director and superintendent. The Gold Medal Sewing Machine Company was firmly established as the largest sewing machine factory in Massachusetts. The last we hear of Albert Johnson in the sewing world is in 1872 when Albert was in court trying to extend his patent rights. Even without Albert's inventive streak, the Gold Medal Sewing Machine Co flourished. Under the direction of Andrew J Clark the range of machines grew and grew. Interestingly as the business expanded in 1877, William L Grout became a partner in the company and later General Manager.

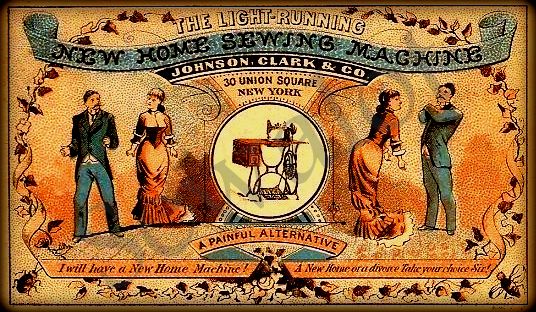

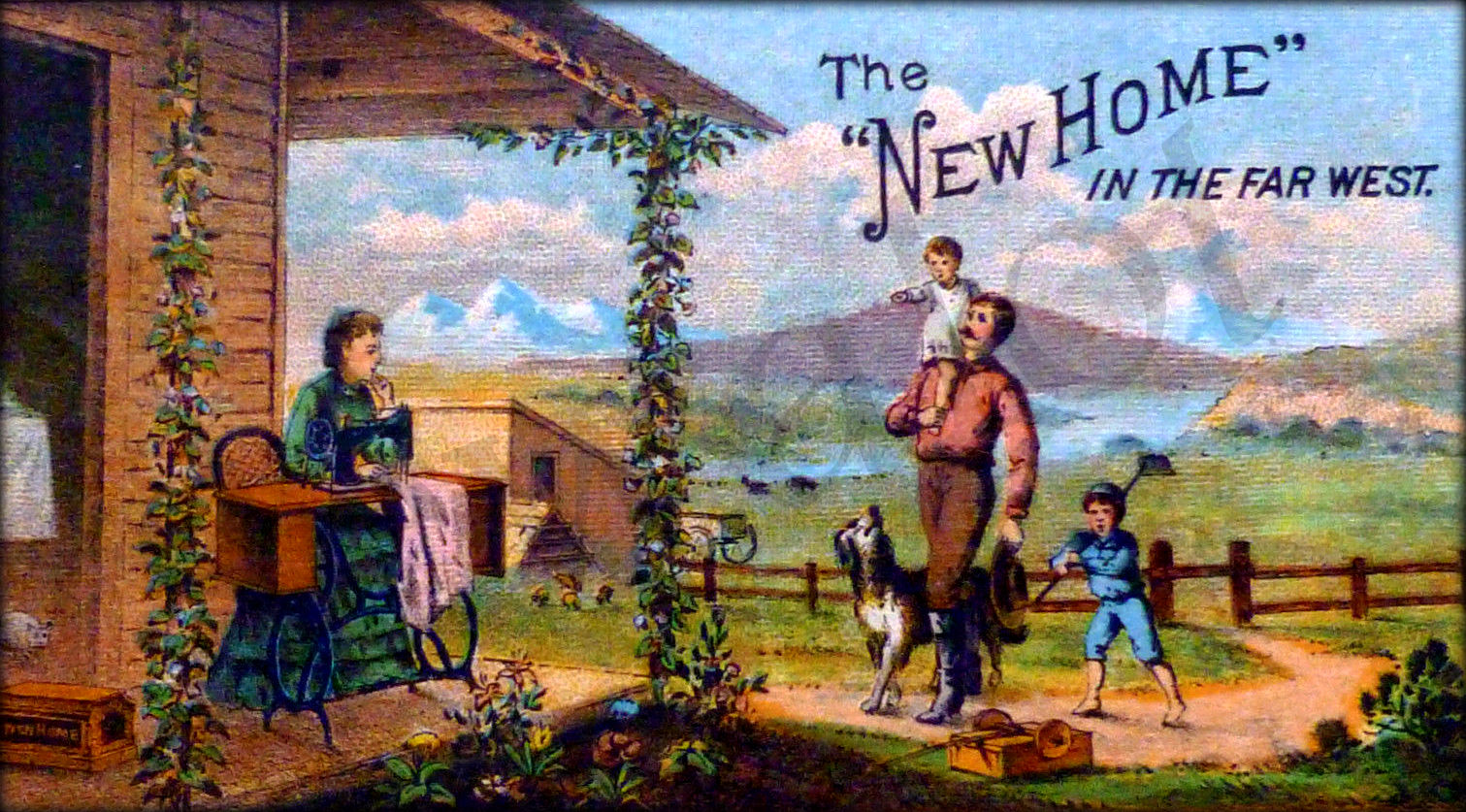

Home Sewing Machines Are Born Johnson Clark & Co, 30 Union Square New York New Home Sewing Machine advert

Although A F Johnson had probably departed from the business the adverts still had his name. He may have even become a sleeping partner or an executive director. He may have simply adopted a back stage position but still had an interest in the companies success. This may explain his continuing patent battle with Gibbs. Of course it was down to his ideas and patents that the firm had existed in the first place. However, all that was about to change with the brilliant Stephen French. In 1868 the works Manager at The Gold Medal Sewing Machine Co, Stephen French, had his patent approved, creating an even better selling machine for the company (which they called the Home Shuttle sewing machine).

By the late 1860s the Gold Medal Sewing Machine Company was producing the Home Shuttle sewing machine, the Home Companion sewing machine, and the Improved Home Shuttle sewing machine and more. The best by far was the Dolly Varden Improved Shuttle sewing machine. I have a special page for that, Dolly Varden Sewing Machine. They were all standard two-thread lock-stitch shuttle machines, which is what most people wanted.

New Home is born The experimentation that Albert Johnson had done with multi-thread, chain-stitch and New England machines in the early years was long gone. The only chain-stitch produced by the Gold Medal Sewing Machine Company from around 1866 was the Octagonal sewing machine, also called the Perfection sewing machine in Europe. The company survived and thrived with their new models. Remember the Home shuttle was a proper lockstitch. It became their first state and country-wide bestseller. It was as if after 25 years the company had come of age. By combining its popular early New England machine that people knew the company for, and the latest Home Shuttle machine, Johnson, Clark & Co became, New Home.

New Home The early trademark of the New Home Company. The sprinting greyhound The name Albert Johnson has long disappeared into sewing machine history. Who could ever believe that one Massachusetts entrepreneur, working away in his shed during the American Civil War, and selling his machines from the back of his pony & trap, has a direct connection to one of the biggest sewing machine companies in the world today! History is fascinating isn’t it? Read the last part and you will find out how. Interestingly for a period New Home had a manufactory in London, England and well as America. I have never seen a Victorian British made New Home, Johnson & Clark. Maybe the Perfection Octagon sewing machine is one of them? The company became firmly established in the market place as New Home around 1881-2. Early in 1882 the Gold Medal Sewing Machine Company was officially renamed the New Home Sewing Machine Company. An incredibly complex story involving dozens of investors, entrepreneurs, engineers, designers and inventors had all at last combined into one successful business making sewing machines. Both Grout and French still remained powerful men in the business. In 1927 the New Home Company merged with The Free Sewing Machine Company and in 1953 merged again with the National Sewing Machine Company. In the late 1950s the giant Japanese Janome Corporation took over the American New Home Sewing Machine Co. They continued using the New Home name on some of their sewing machine up into the new millennium. That as they say is that! I hope you enjoyed the journey. I need pills and a dark room for a week! Bye for now. A brief history of A F Johnson and New England sewing machines by Alex Askaroff

|

||||

|

Well that's it. I do hope you enjoyed my work.

If you have any information that you would like added

I would love to hear from

you:

alexsussex@aol.com

OUT NOW! Raymond-Weir New England sewing machines Most of us know the name Singer but few are aware of his amazing life story, his rags to riches journey from a little runaway to one of the richest men of his age. The story of Isaac Merritt Singer will blow your mind, his wives and lovers his castles and palaces all built on the back of one of the greatest inventions of the 19th century. For the first time the most complete story of a forgotten giant is brought to you by Alex Askaroff. News Flash! Alex's books are now all available to download or buy as paperback on Amazon worldwide.

"This

may just be the best book I've ever read."

"My five grandchildren are

reading this book aloud to each other from my Kindle every Sunday.

The way it's written you can just imagine walking

beside him seeing the things he does. News Flash! Alex's books are now all available to download or buy as paperback on Amazon worldwide. Fancy a good FREE read: Ena Wilf & The One-Armed Machinist

See Alex Askaroff on YouTube demonstrating antique sewing machines. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8-NVWFkm0sA&list=UL Hi Alex I Enjoyed your page! My Family on my Father's Side sold New Home Sewing Machines, around the turn of the century up to WW1 era. My Grandfather would go to fairs, carnivals, and other open events, and demonstrate the machines, by doing fancy free motion embroidery with a treadle machine, no less! Ena, Wilf and the one-armed Machinist Don't you just love this scene.

|

||||

|

|

See Alex Askaroff on Youtube http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8-NVWFkm0sA&list=UL

|

|

||

|

||||